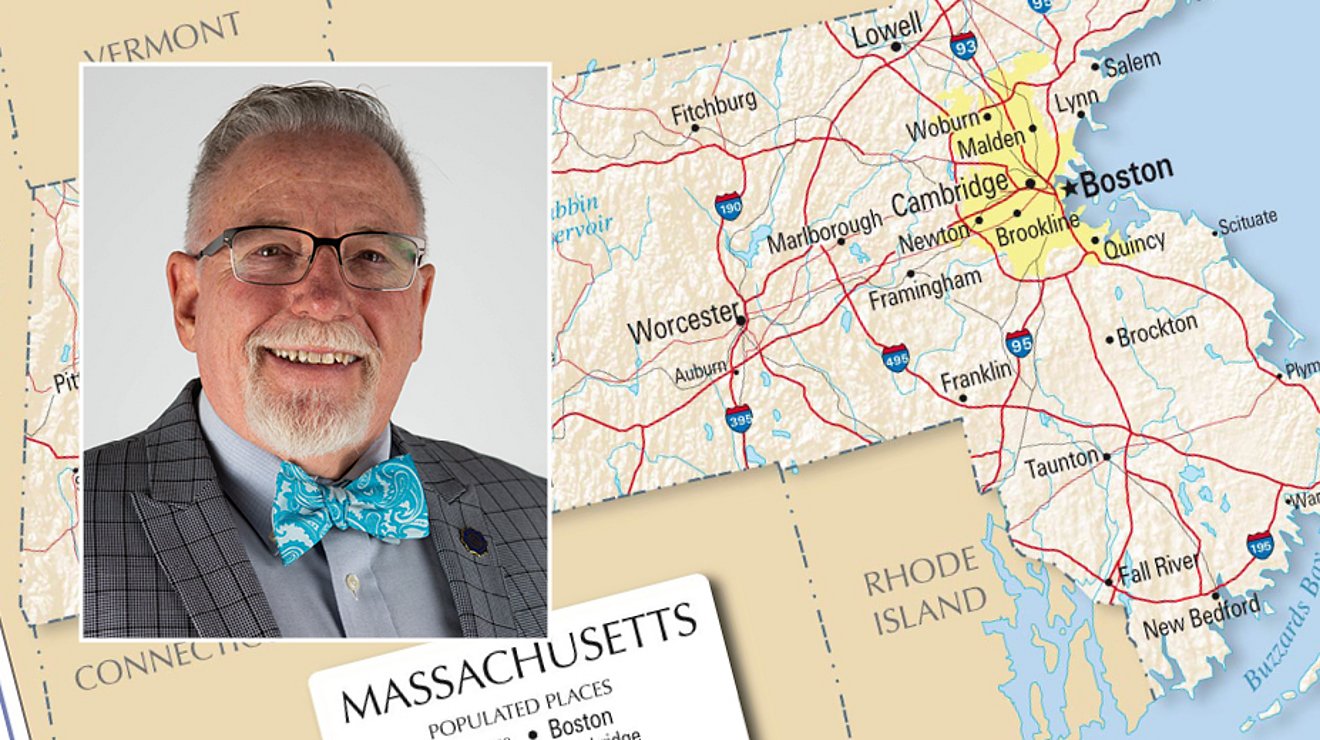

Dr. Mark Wilkinson, professor of nursing at Lubbock Christian University, landed in Boston, Massachusetts on April 28, ready to help fight COVID-19 on the frontlines—and preparing to share his experiences with the students in the two online courses he is still teaching.

“Ever since the pandemic broke out, there was so much need, especially here in the northeast for nurses, and I felt compelled that I could, should, do something,” shared Wilkinson. “So, I began to look into what specific needs there were that I could fill and started looking into what was out there.”

His background is in community health, and he quickly ran across a group who specializes serving nursing homes and long-term care facilities in the northeast. The time commitment—this contract is for up to eight weeks, where most others range from 16-18—along with the nursing homes he’d be working in, convinced Wilkinson that this was where he needed to be. “They don’t get the same highlight as the intensive care units in New York do,” he explained, “but they’ve been hit really hard. The commonwealth of Massachusetts contracted with this company to go into the long-term care facilities to try to help the situation there.”

Wilkinson explained that there are approximately 383 nursing homes in the state of Massachusetts, and currently over 300 of them have COVID-positive patients. “Not only have the patients there been affected, but the staff as well,” he said. Many staffers in the nursing homes in which Wilkinson is working have tested positive for the virus, and have had to go home, unable to work until they’ve both recovered and also tested negative for the virus. “So, the staff here was already dropping—they didn’t have anyone else. That’s where we came in, to help take the place of those members, to ease the burden because everyone there is overworked.”

Because his team is working in COVID-positive environments, they have to wear all of the protective equipment the entire time they’re in the homes. The team was told they’d be working 12-hour shifts, but the days don’t always adhere to any particular time clock.

Because his team is working in COVID-positive environments, they have to wear all of the protective equipment the entire time they’re in the homes. The team was told they’d be working 12-hour shifts, but the days don’t always adhere to any particular time clock.

“We’re working 12-hour shifts—until you’re done,” he said. Each team is supposed have ten members, composed of a couple of RNs, a few LPNs, and some CNAs, because they need all levels of expertise. “We have a group of seven,” Wilkinson explained, “because a couple of people didn’t make it—one tested positive before we started, and two others decided this was too hard and they didn’t want to do it.”

The team only spends four or five days at each facility before they move on to the next one. “Last night, I finished my last shift at the place we’ve been at, today I have a day off, and then tomorrow we’ll head on to the next one,” Wilkinson said. “The government wanted us to come in, give some relief, and then move on to the next home because the need is so great,” he emphasized. “The unit I’m in is tasked with covering the entirety of western Massachusetts.”

Wilkinson’s wife and a daughter stayed behind in Lubbock, but they’re staying connected. “All three of my kids are adults, and I also have six grandkids,” he said. “I’m still teaching my classes online—in fact, I’m actually grading a paper right now.”

That was a big part of why the eight-week limit was so important to his search. “I’m finishing teaching two online course right now for LCU students—Community Health I, and Community Health II—and then I’ll be starting three more at the beginning of the summer term.”

When asked whether he was able to share some of the experiences he was having on the ground in the northeast with his students, his answer was a resounding yes.

“Absolutely—that was one of my motivations,” he said emphatically. “I teach Community Health, and one of the courses I’ll be teaching this fall in the Nurse Practitioner master’s program is Applying Best Practices. One of the things that I wanted to do is research how the state responded to the crisis and evaluate if the response really worked. That’s one of the things that we do at the master’s level, go in and look at a policy, and then ask, ‘Did that actually work?’ It might look great on paper, but we evaluate a policy’s true effectiveness.”

Wilkinson shared that one of the hardest things about his work in Massachusetts is that the people who succumb to the virus are dying alone because of the quarantine. “Their family can’t be there with them,” he said. “Sometimes the family comes and stands at the window and waves at their dying relatives.”

He continued, “I think one of the hardest things is that these are older people—grandmas and grandpas—and a lot of them are confused. They don’t understand why no one can come visit them, but they feel sick, they feel horrible, they don’t understand what is going on, and the people who are treating them are wearing space suits. They’re afraid, and they’re alone. There’s one little lady who has Alzheimer’s, and she just walks up and down the hall and cries. I walked up to her when I first saw her in my protective gear and just gave her a big hug, and she just sort of melted into me. These people don’t get a lot of physical contact.”

The conditions are tough, and the stories of those he’s helping can be heartbreaking.

“One lady here sits by the sliding glass door every day to have lunch with her husband, but she’s confused and doesn’t understand why he has to sit outside while she’s inside,” he shared. “When he leaves, though, she’s a wreck, and is really, really hard to deal with—it’s really hard to watch, because she’s so upset, and doesn’t understand what’s going on.”

“That’s one of the biggest differences between us and those nurses and doctors in hospitals,” he continued. “It’s hard enough dealing with this virus with sane, coherent patients—these we’re working with don’t know what’s going on, and it makes everything so much harder. I brought something up with my spirituality class—that in cases like these, it’s so much more important that we’re addressing the spiritual needs of our patients. There is no one else, you’re it. There’s no one else who is going to have any connection with these people. That’s why I emphasize holistic health that touches people. We get so involved in the technical side of our nursing that sometimes we can forget the heart of it. We hide behind a computer and talk to the screen, not the patient. That’s why I emphasize the other side of it, the heart of nursing, that really cares about the people and what’s going on in their lives.”

The “heart of nursing” is really what Wilkinson is finding to be the most powerful experience during his time in Massachusetts.

He explained that he shares a short devotional thought in each of his classes. For one of those he is currently teaching, Quality of Nursing, he pointed out that, where Jesus could have referenced a number of things as proof of his identity, he simply told John the Baptist of the healing he was doing—he identified the way he cared for others as proof of who he was.

“I believe that part of what sets us apart at LCU is that we’re supposed to be serving—that’s part of our motto. How will they know we’re different, if we don’t show genuine care? Jesus didn’t tell John about his doctrine, or the prophesies, or about what his church looked like—he said, ‘Let me show you how much I care.’ As a church, and as a university, the way that we’re going to impact the world is not because we have great doctrine—it’s because we have great care.”

“It’s like that old saying,” he added, “‘No one cares how much you know unless they know how much you care.’ No one wants to listen to us about doctrine if we’re not out there loving and taking care of people—and I feel like that’s one of the most important things that I can bring back to share with my students.”